This post was originally published on Healthy Forest

Don Healy graduated from Oregon State University in Forest Management in 1968. The three years following graduation were spent in the U.S. Army as it was the Vietnam War Era and it was better to volunteer than to be drafted. He worked for Boise Cascade in Northeast Oregon from 1971 to 1978 as an Acquisitions Forester where he led a program to prepare inventories, valuations and management plans for private landowners in the region. After the company’s operations were shut down due to the reduction in federal timber supply, he became a financial advisor in Everett, Washington. Don remains active on forestry issues. He says you can take the forester out of the forest, but not the forest out of the forester.

“It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble.

It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so”

Mark Twain

The battle over the proper management of the forested resources in the United States has been going on for over 65 years with no resolution in sight. Our society is now paying the price with increased forest fire activity, increased insect and disease issues and other indicators of the decline in the overall health of our forest resource. It is essential that we come to a consensus as to the appropriate manner in which to actually address this complex issue. To start, we need to mine down to the facts so we can have a solid foundation for a reasonable discussion. One of our fundamental problems is that so much of the public’s perception of the state of this resource is simply not correct. As the quote of Mark Twain’s above states, these misconceptions pose a major hurdle in resolving the issues involved. The following are some points that are of concern:

1. The amount of forested area in the U.S. and the trend in the area over recent history. Are we losing or gaining forested area?

2. The trend in the volume of timber in the U.S. over recent history.

3. How many acres of old growth, mature and younger stands do we have?

4. What is the causing the demise of old growth stands?

5. The cause and solution to the increasing wildfire problem.

6. Addressing insect and disease issues as part of the forest management equation.

7. The very real possibility that in the future we will need to rely upon our domestic forested areas to meet the wood products needs of our nation.

Only after we determine and agree upon the basic facts about our forested lands, the inventory, can we work towards a consensus of what, if any actions, should be taken on individual tracts of land. As an example, old growth stands are a very important segment of this equation. Currently, there appears to be no target for what portion of forest lands should ultimately remain or become old growth. Thus, when the BLM or USFS propose silvicultural actions necessary to reduce fire hazards or other issues in mature forests that possibly might become old growth in the future, these actions are countered with lawsuits, and nothing gets accomplished. Reviewing the points above we find that:

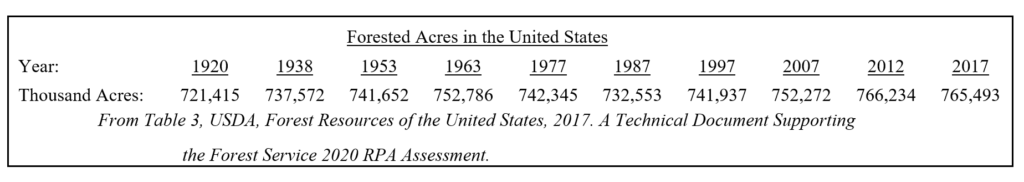

1. Forested Area: “The U.S. Census Bureau reports the total land area of the continental United States and Hawaii (excluding the Caribbean Islands and U.S. territories) as 2.3 billion acres. Forests and woodlands combined occupy 822.5 million acres of the U.S. land base. Of those, 93 percent (765.5 million acres) meet the international definition of forest, with the remaining 7 percent recognized as woodlands. Thus, forests comprise 34 percent of the American landscape, and forests combined with woodlands comprise 36 percent.”

The perception by most is that our forested acreage has diminished. The reality is that we have gained 44,078,000 acres since 1920, a gain of 6.1%

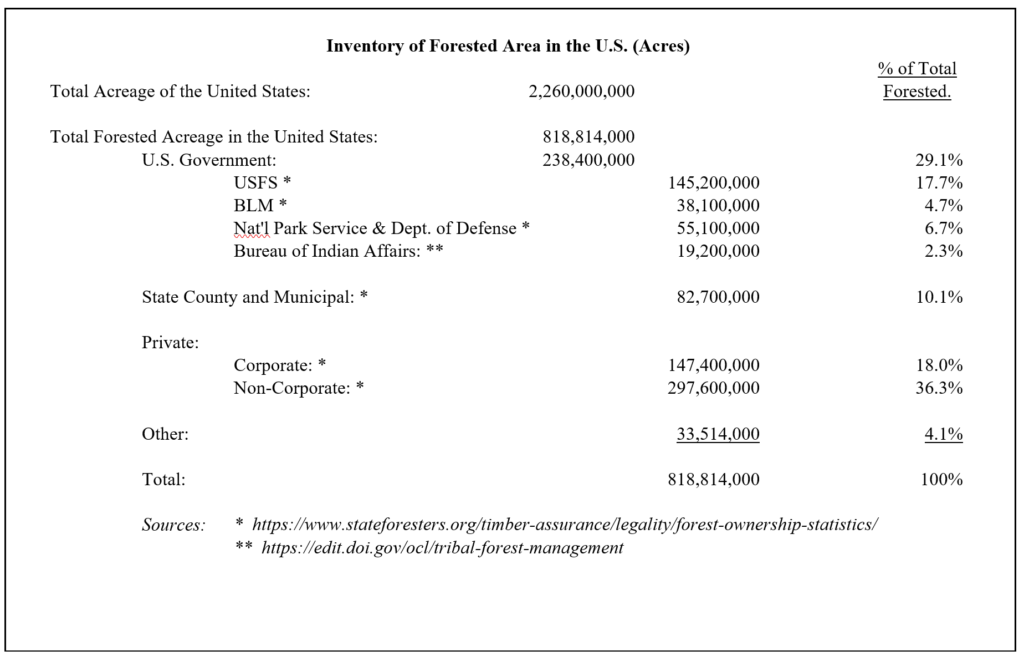

There are numerous owners and administrators of the forested lands within the United States as shown in the chart below:

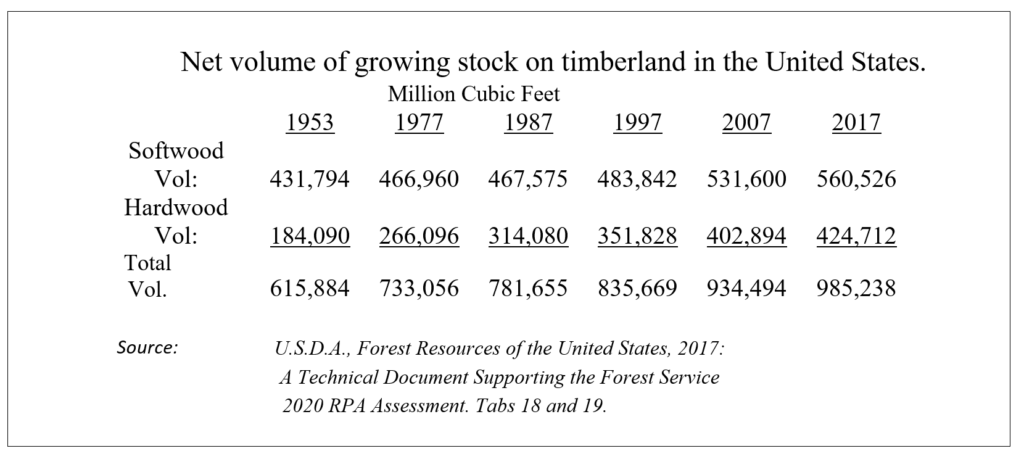

2. Timber volume trend in the United States: Again, the perception of many is that our timber supply has diminished as well. The chart below shows just the reverse.

With the dramatic reduction in harvesting on federal lands commencing in the late 1970s we have watched the volumes of merchantable timber increase by 60%. On federal lands, we quit harvesting, but the trees kept growing. U.S. wood products needs have been met in large part with Canadian imports which in recent years have reached $40 billion per year. During the past 45 years with very little forest management occurring on federal lands, we have seen an increase in insect and disease issues, stagnation in some stands and the resultant increase in wildfires.

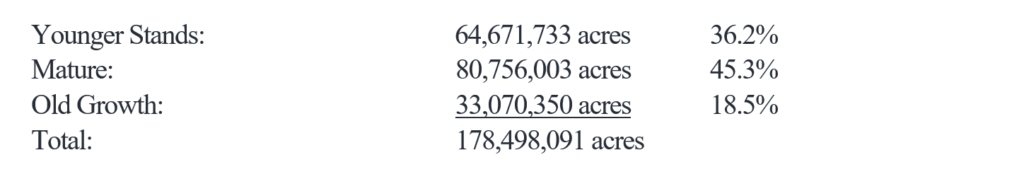

3. Inventory of old growth, mature and younger stands: Currently, on federal lands administered by the U.S.F.S. and the BLM we have the acreages in the following forest classifications:

So currently, 63.7% of the forested acreage managed by U.S.F.S. and the BLM is currently old growth or mature stands.

Note: The acreages listed in the above charts vary slightly because they were measured by different agencies at different times, but the differences are not significant for our purposes here.

4. Old growth stands and their perils: The obvious need to reduce the fuel load in our nation’s forests to reverse the upward trend in wildfires is met with resistance from the environmental community. The focal point of this concern generally involves old growth forests. In the past 60 years, the definition of old growth has changed considerably. In forestry school in the mid-1960s we were taught that an old growth forest was a mature forest in which the amount of growth was slowing to the point that it was equaled by the amount of mortality. Currently, the old growth label is applied to stands as young as 150 years old. While old growth forests are important for numerous reasons, carbon sequestration is frequently a top consideration as one of their benefits. However, when discussing a fully mature old growth forest, this is not correct. In individual trees, and even-aged forests such as the Douglas-fir common to much of the western United States, the growth pattern follows that of a sigmoid curve. Very slow growth in the early years, followed a sustained period of consistent growth, followed by a decline to a static condition before death. In a typical old growth forest, we see downed timber and a much greater incidence of decay. Obviously, an old growth forest has less utility as a carbon sink than does a vibrant, middle-aged stand.

4. Old growth stands and their perils: The obvious need to reduce the fuel load in our nation’s forests to reverse the upward trend in wildfires is met with resistance from the environmental community. The focal point of this concern generally involves old growth forests. In the past 60 years, the definition of old growth has changed considerably. In forestry school in the mid-1960s we were taught that an old growth forest was a mature forest in which the amount of growth was slowing to the point that it was equaled by the amount of mortality. Currently, the old growth label is applied to stands as young as 150 years old. While old growth forests are important for numerous reasons, carbon sequestration is frequently a top consideration as one of their benefits. However, when discussing a fully mature old growth forest, this is not correct. In individual trees, and even-aged forests such as the Douglas-fir common to much of the western United States, the growth pattern follows that of a sigmoid curve. Very slow growth in the early years, followed a sustained period of consistent growth, followed by a decline to a static condition before death. In a typical old growth forest, we see downed timber and a much greater incidence of decay. Obviously, an old growth forest has less utility as a carbon sink than does a vibrant, middle-aged stand.

Again, the perception and the reality vary considerably. “While timber harvesting is recognized as the historical cause for loss of much of the nation’s mature and old-growth forests, current data show that in recent decades the leading cause for losses on forestlands managed by the Forest Service and BLM is from wildfires.” Between 2000 and 2020 losses due to forest fires were 3.2%, insects and diseases were second at 2.3% , while tree cutting was only amounted to 0.3% “ (Source: Mature and Old-Growth Forests: Analysis of Threats on Lands Managed by the Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management in Fulfillment of Section 2(c) of Executive Order No. 14072)

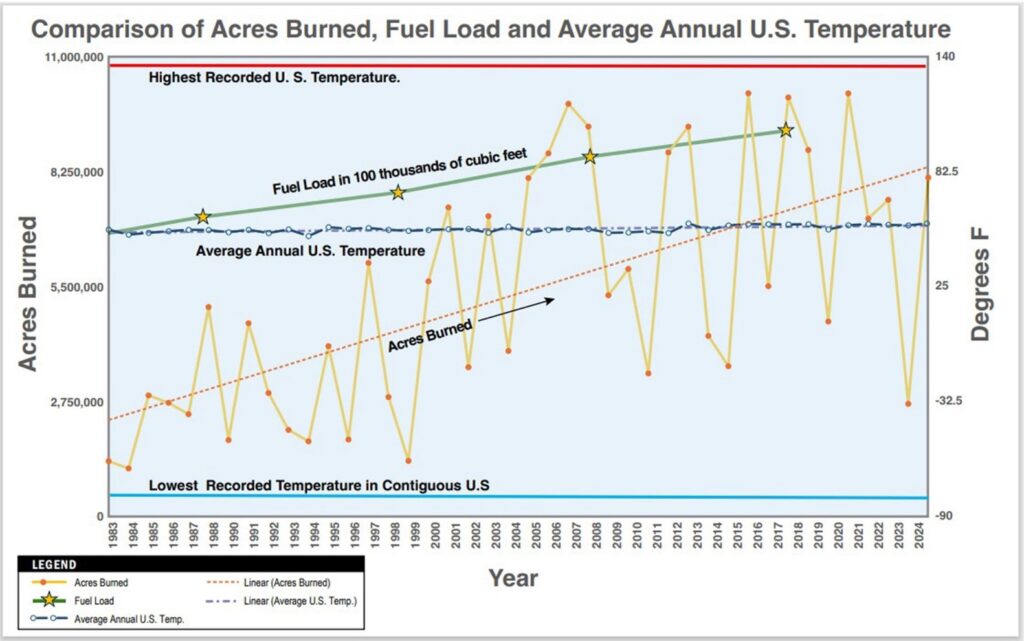

5. The cause and solution to the increasing wildfire problem: The following chart spells out in graphic detail the relative relationships between the two most frequently cited causes of the recent increase in wildfires; fuel load and climate change. The increase in timber volumes mentioned in section 2 above is used as a proxy for fuel load in this chart although it probably understates the issue considerably due to two factors.

- With very little management of federal lands for the past 45 years, the volume of grasses, shrubs, and smaller timber classes, of which we have no measure, have probably grown even more rapidly.

- The CO2 fertilization effect has impacted all vegetation. As an example, the birch tree in my yard is growing 20% more rapidly today than it was in 1960. To see how this effect might be affecting your favorite trees or plants please see: (www.co2science.org/data/plant_growth/plantgrowth.php).

The center, dashed line plots the average annual U.S. Temperature on a rational scale against the highest and lowest temperatures recorded for the United States. This indicator appears as a virtual flat line, while the fuel load and acres burned lines show significant upward trends. Yes, the scientific maxim that “correlation does not prove causation” is true, but science has already proven that fuel load is one the three requirements for fire.

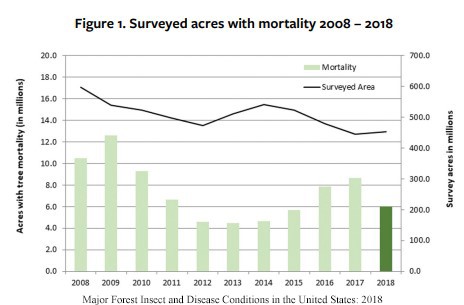

6. Insect and Disease Issues: While the wildfire problem gets lots of press and is the focus of public concern, the losses caused by insects and disease natural to the forest environment are equally damaging, more insidious and contribute to the wildfire risk. From “Major Forest Insect and Disease Conditions in the United States: 2018”: “In 2018, more than 6 million acres of tree mortality was caused by insects and diseases in the United States, which is approximately 2.6 million acres less than reported in 2017. In forests across the western United States, tree mortality by fir engraver accounted for 33 percent of total mortality observed in 2018, causing approximately 1.9 million acres of mortality to white, red, and grand fir. Spruce beetle, emerald ash borer, and sudden oak death were also important sources of tree mortality throughout our Nation’s forests in 2018.” The graph below shows the mortality figures for the prior 10 years. (Forest Insects pdf Page 1.)

“In 2022, more than 8.4 million acres with tree mortality caused by insects and diseases was observed in the United States. A total of 462 million acres of forests were surveyed in 2022. The total tree mortality reported in 2021 was 5.8 million acres with 423 million acres of forests surveyed.” (Major-Forest-Conditions-2022.pdf Page 1.)

The author had a personal association with two historic significant insect problems. One being the tussock moth, a defoliator that reappears on a roughly 9-year cycle with outbreaks of varying intensities. “Another regional tussock moth outbreak affected the Umatilla National Forest in the early 1970s. Initial damage was noticed as 2,400 acres of defoliation in the Okanogan Valley of north-central Washington in 1971. In 1972, over 197,000 acres were defoliated in Oregon and Washington. Perhaps some of the worst tussock-moth damage in this early-1970s outbreak occurred on the north end of Umatilla National Forest. By 1974, 44% of defoliated acreage in the entire outbreak area (including state, private, and other federal ownerships) was on the Umatilla National Forest – 353,850 acres out of a total outbreak area of 800,000 acres!” ( tussock moth fseprd7166465.pdf Page 4.)

The mountain pine beetle has been a major problem in the western U.S. and British Columbia for centuries, with extensive infestations continuing over the past 60 years. More recently related beetle species have been wreaking havoc over a broader geographic area. “First, mountain pine beetles devastated lodgepole and ponderosa pine trees across western North America. Then came spruce beetles, which have targeted high-elevation Engelmann spruce, spreading from New Mexico into Colorado and beyond. Altogether, with their advance fueled by climate change, bark beetles have ravaged 85,000 square miles of forest in the western United States — an area the size of Utah — since 2000. Pine beetles also have killed trees across roughly 65,000 square miles of forest in British Columbia, and in the southeastern U.S., they have caused millions of dollars of damage to the timber industry in states such as Alabama and Mississippi.

The beetles are now advancing up the Atlantic coast, reaching New York’s Long Island in 2014 and Connecticut the following year. A new study projects they could begin moving into the twisting pitch pines of New England and the stately red pines of Canada’s Maritime provinces by decade’s end. Warming winters could push the beetles north into Canada’s boreal forest within 60 years, climate scientists say.” (https://e360.yale.edu/features/small-pests-big-problems-the-global-spread-of-bark-beetles)

To put this into perspective, the 85,000 square miles of affected area in the western U.S. equals 54,400,000 acres. In 2024, the area affect by forest fires in the U.S. was just over 8,000,000 acres. So, pine beetles have impacted about 7 times the area affected by wildfire this year.

The overall impact of insect and disease agents is quite stunning. From an AI generated answer to a Google question: “According to research from the US Forest Service, there are hundreds of native and non-native insect and disease species that attack US forests, with one study identifying over 300 different insect and disease agents impacting tree species across the continental United States and Alaska.” The average citizen just doesn’t get a feel for the extent of the issue. Forests are viewed as tranquil, relatively stable environments. The reality is that “it’s a jungle out there” and for most forest land managers the worry isn’t might we be impacted by an insect or disease issue, but how hard will we get hit, by which predator, and how do we respond.

Many insect and disease issues can be controlled or mitigated with proper silvicultural practices. The healthier our forested areas are, the greater the ability of the trees to resist and survive both bark beetle attacks and defoliating insects such as the tussock moth. For 45 years now, thinning and selective harvest operations on federal lands have been severely curtailed. As a result, many areas are over-stocked and/or stagnating creating ideal conditions for massive infestations and at the same time dramatically increasing the forest fire risk.

7. The very real possibility is that in the future we will need to rely upon our domestic forested areas to meet the wood products needs of our nation. In the late 1970s, due to the actions of many in the environmental community, our forest products industry was decimated. What we see around us today is but a shadow of what once was a thriving industry and significant part of our economy. However, the contraction of our forest products industry did not in any way reduce our need for lumber, paper, cardboard and a myriad of other products. Our neighbor to the north, Canada, expanded their forest products industry to counter the reduction. British Columbia stepped up their production of wood products. However, recent articles from Canadian sources indicate that to profit from our demand, the Canadians while remaining within the sustained yield limits concentrated their logging efforts in areas with larger trees, commonly the old growth stands. With the easy pickings now eliminated, future logging operations in the smaller size classes have marginal profitability and the timber companies are turning towards greener pastures. The links below are to various news articles addressing the timber supply and forest products industry in British Columbia.

See:

https://www.nsnews.com/highlights/british-columbia-logged-a-fifth-more-old-growth-forests-than-reported-7640977

https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/canada-forests-climate/

https://www.biv.com/news/resources-agriculture/satellites-track-loss-old-growth-forests-bc-government-said-it-would-protect-8272625

https://vancouverisland.ctvnews.ca/clear-cut-of-vancouver-island-ancient-trees-shows-faults-in-b-c-s-deferral-system-says-conservationist-1.6399513

https://www.cbc.ca/amp/1.6604830

https://globalnews.ca/news/10831523/canfor-loss-350-million/

https://thetyee.ca/News/2024/10/30/Inside-Fight-Save-Forestry-Jobs/

Quote from last article: “Over the last two decades, forestry jobs have fallen roughly by half as mills have closed across the province (BC), dropping from around 79,000 in 2001 to 44,000 in 2023.”

To ensure our domestic needs in the future we will need to increase the harvest levels in our forests. Handled properly, this can be an opportunity to improve the health of our forests and a benefit to our economy. However, we first must rebuild our forest products to modest levels. We don’t need to return to the levels that existed prior to the 1970s, but our current wood products infrastructure is insufficient to fill the gap. This should be viewed as an opportunity, not a problem. We should be constructing newer, more efficient mills and utilizing the many advances available in engineered lumber products. Rather than clear-cutting, we should be using selective cutting and thinning methodologies, using feller bunchers and similar, less intrusive harvesting techniques to treat the land more gently.

Action Plan: Now that we have an inventory of the overall forest resources of the United States, we need to develop a process to determine what our goal is for the future distribution of , and possible uses for these lands such as:

- Timber production

- Recreation

- Old growth

- Rehabilitation

- Wilderness

Of the 238,400,000 acres currently administered by the U.S. Government, 74,300,000 is already under the jurisdiction of the U.S. Park Service, the Department of Defense or the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Of the 178,498,091 acres under the management of the USFS and BLM, 113,826,353 acres are classified as mature or old growth. So, the reality is that almost 14% of the total forested acreage of the United States is classified as old growth or mature. Of the forested area managed by the USFS and the BLM, the portion of federal lands that we are attempting to determine the future management direction of, 63.7% is classified as mature or old growth. Additionally, a portion of the lands under the management of the National Park Service, the Department of Defense and the Bureau of Indian Affairs as well as state, county, municipal or corporate ownerships would also qualify as mature or old growth. We just don’t happen to know what those acreages might be and don’t have control over their future disposition.

In reviewing the amount of, and the trend of forested area in the U.S. the situation is very positive. The U.S. has 44,078,000 more acres of forest than it did in 1920. Likewise, the volume of merchantable timber in the U.S. has been increasing quite rapidly in recent decades and is now 60% greater than it was in1953. On BLM and USFS lands mature and old growth stands make up almost 64% of total area. The major problems we are facing involve increasing wildfires and the insect and disease issues that are cyclic, but common and indigenous to the forest environment. Ironically, the greatest risks to old growth and mature timbers stands are fires and insects and diseases.

The time has long since past when we need to come to a consensus on what an acceptable allocation of our federal forested lands to the various uses listed above should be. Once that is decided, we need to then create a management plan that identifies those parcels best suited to be managed, or not managed, to achieve that goal. Since mature and old growth stands seem to draw the most public attention, coming to a consensus on the amount and those specific tracts that should be preserved would be the first order of business. Then if the current amount does not meet with the consensus figure, identify and set aside those areas with management plans to fulfill that objective. All in all, if would appear that we don’t really have a deficit in that classification. Our current levels of these classes seem very reasonable relative to other developed nations, but being public lands, this needs to be decided by a democratic process. In Europe, only 3% of the forested area is mature or old growth. Once this step is taken, then we simply work our way down the list, which we probably require some adjustment of prior allocations along the way.

However, we do need to realize that the public perception that old growth and mature stands are relatively immune to anything other than the chain saw is, like Mark Twain pointed out, is simply not true. Fire and insect and disease issues are much more damaging.

Once we go through the allocation process, we then need to prepare suitable management plans for each classification and then adhere to those decisions unless nature intervenes. The management plans also need to address the reality that forest fires are a serious and growing concern, and that insect and disease issues will arise and need to be addressed and that mature and old growth are no less resistant to these issues than are younger forests.

As pointed out earlier, it is very likely that in the not-too-distant future the United States will very likely have to become more self-reliant upon our own forest resources to meet our lumber, paper and wood products needs. We’ve been relying on the Canadians for many decades, but their wood products industry is already in decline. Our problem is just the opposite. We have a very ample timber supply, but we don’t have the forest products industry to fill our own needs. The rebuilding of a portion of our forest products industry to fill this need will require the guarantee of a stable timber supply. Industry will not invest if the supply is inconsistent and undependable. Additionally, proposed timber sale cannot be dependent upon the whims of environment groups and judges, and the anarchists’ approach to interrupting harvest activities can be tolerated no longer.

We’ve dawdled long enough, the time is now at hand when we need to seriously address this issue and apply sound forest management concepts and practices to this very vital national treasure for the benefit of our citizens and future generations.

Source: Healthy Forest

0 Comments