This post was originally published on Eco Watch

Quick Key Facts

- Climate fiction, cli-fi for short, refers to stories in whatever genre or medium that respond to human-caused climate change.

- Journalist Dan Bloom claims to have coined the term in either 2007 or 2011.

- Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, which many define as the first science fiction novel, was influenced by climate change caused by the eruption of Mount Tambora in 1815.

- Perhaps the first novel to address anthropogenic global warming as currently understood was Arthur Herzog’s Heat, published in 1977.

- Ecofiction, a related genre to climate fiction, emerged in the 1960s and 70s in response to the popularization of ecology and the birth of the modern environmental movement.

- The novel Bloom first marketed as cli-fi, Polar City Red, was a dystopian story about climate refugees in 2075 Alaska.

- Solarpunk is a subgenre of climate fiction that focuses on positive futures reliant on renewable energy.

- Of the 13 2024 Academy Award-nominated feature films that take place on present day Earth, three acknowledged climate change.

- People who saw the 2024 film The Day After Tomorrow were more likely to be concerned about climate change and change their habits and even voting patterns accordingly.

- The website Grist operates a yearly short story contest titled “Imagine 2200: Climate Fiction for Future Ancestors.”

What Is ‘Climate Fiction’?

Climate fiction is a genre of fiction that emerged in the first decades of the 21st century in response to growing awareness of the climate crisis caused primarily by the burning of fossil fuels. It is often abbreviated as “cli-fi.”

As the term “cli-fi” suggests, climate fiction was originally highly associated with science fiction and often features scientist protagonists or the latest climate science to offer imaginings or warnings of what the near or far future might look like if humans do or do not act to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. However, as the impacts of climate change have intruded ever more into daily life, the genre has evolved to include many works set in the present or near-present as well. Climate fiction is a diverse gathering of works that ranges from Hollywood disaster thrillers, like The Day After Tomorrow, to hard science fiction focused on technological and political change, such as the works of Kim Stanley Robinson, to introspective literary novels, like Jenny Offill’s Weather.

Jenny Offill’s novel Weather. Wolf Gang / Flickr / CC BY 2.0

How Did Climate Fiction Emerge?

Extreme weather events have inspired human literature from its origins. The Mesopotamian Epic of Gilgamesh, the oldest surviving work of written fiction, features a description of a great flood that drowned all but one surviving human. Scholars have pointed to the similarities between this and the Noah’s Ark story in the Bible, and believe both may have been inspired by a real flood in the Tigris and Euphrates Valley between 5,000 and 7,000 years ago. There is also a tie between climate chaos and the birth of science fiction. In 1815, the ash plume from the eruption of Mount Tambora caused so much global cooling that 1816 came to be known as the “year without a summer.” It was this year that Mary Shelley wrote Frankenstein — widely considered the first science fiction novel — while rained in in a Genevan villa with fellow writers Percy Shelley and Lord Byron. While the novel itself doesn’t deal with climate change, stormy weather is a constant motif, and scholars argue that Shelley based the creature’s appearance and ill-treatment on the sickliness of and poor reaction to people displaced by famine in the wake of the eruption. The “year without a summer” also inspired Byron to write a poem called “Darkness,” which imagined a world without a sun.

Shelley and Byron did not know what caused the weather disasters that inspired their 1816 works. While earlier myths and stories, such as the biblical flood narrative, would depict weather extremes as a supernatural punishment for human behavior, it was not until the 19th and 20th centuries that scientists figured out that human society could and would alter the climate by burning fossil fuels. While end-of-the-world narratives were popular in early science fiction — such as Shelley’s The Last Man (1826), M. P. Shiel’s The Purple Cloud (1901) and Sydney Fowler Wright’s Deluge (1928) — these imagined that end brought by disease (in the first two examples) and earthquake-caused flooding. One early example of science fiction dealing with human-caused environmental devastation is Laurence Manning’s 1933 serial The Man Who Awoke. In one episode, the titular time traveler encounters a sustainable civilization that has recovered from “a civilization of waste” that sounds eerily like our own: “Fossil plants were ruthlessly burned in furnaces to provide heat; petroleum was consumed by the billion barrels; cheap metal cars were built and thrown away to rust after a few years.” However, Manning notably does not consider the impact of all those fossil fuels on the climate.

Lawrence Manning’s The Man Who Awoke was published in 1933. Ballantine Books / Dean Ellis

As the 20th century progressed, more and more science fiction novels began to consider both altered climates and ecological catastrophe. One important precursor for climate fiction is J.G. Ballard’s quartet of novels from the 1960s — The Wind From Nowhere, The Drowned World, The Burning World, and The Crystal World — which imagine the Earth fundamentally altered by wind, flooding from solar radiation-melted ice caps, drought, and the crystallization of matter respectively. While only The Burning World’s drought is human-caused, the themes and motifs of the novels have gone on to influence contemporary authors responding to anthropogenic climate change.

J.G. Ballard’s 1962 novel The Wind From Nowhere. Jim Linwood / Flickr / CC BY 2.0

Perhaps the first science fiction novel to incorporate anthropogenic global warming as currently understood is Arthur Herzog’s Heat, published in 1977 after interviews with several climate scientists and focused on an engineer coming to understand the consequences of rising atmospheric carbon dioxide levels.

Arthur Herzog’s Heat was published in 1977. Simon & Schuster

Another important early work of climate fiction is Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower and Parable of the Talents duology from the 1990s, in which she imagines characters trying to survive in a 2020s California wracked by climate change and economic instability. The novels include the rise of a Christo-fascist president who responds to the chaos with a promise to “make America great again,” bringing chills to many readers when the actual 2020s approached.

Outside of science fiction, Caren Irr has also traced the origins of climate fiction to the tradition of non-fiction environmental writing in the U.S. One strand of this tradition begins with Henry David Thoreau’s Walden (1854), and its close observations of nature made by a solitary narrator, a tradition taken up by authors like Edward Abbey in Desert Solitaire (1968) and Annie Dillard in Pilgrim at Tinker Creek (1974). Many cli-fi authors also focus on “subjective human responses” to the non-human world, Irr argues. Even in dystopian settings or disaster zones, characters will ruminate on the changes or survive in isolation in scenes reminiscent of Thoreau. The other strand emerges from Rachel Carson’s groundbreaking 1962 account of the dangers of pesticides, Silent Spring. In particular, Carson’s otherwise non-fiction account opens with a “Fable for Tomorrow” that describes how the use of pesticides ruins the health and ecosystem of an archetypal U.S. town until there are no birds, pollinators, crops, or fish. It concludes: “No witchcraft, no enemy action had silenced the rebirth of new life in this stricken world. The people had done it to themselves.” This, according to Irr, prefigures two major themes of cli-fi novels: human culpability and survival in a “possibly irrevocably damaged world.”

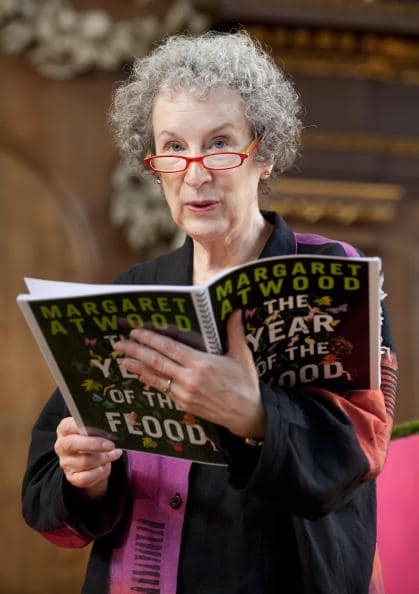

However, as Sherryl Vint points out, it wasn’t until the beginning of the 21st century that climate change itself, as opposed to pollution generally, came to be depicted as the primary cause of the ecological apocalypse. The term cli-fi itself has been traced to journalist and novelist Dan Bloom, who has claimed on different occasions to have coined it in 2007 and 2011, and used it to promote the 2012 book Polar City Red by Jim Laughter. Prominent author Margaret Atwood, some of whose works have also been described as cli-fi, shared a link to that book on social media along with a definition of cli-fi, which she attributed to Bloom. Another early use of cli-fi came from Wired author Scott Thill, who used it in 2010 to describe the Syfy channel movie Ice Quake, about a cataclysmic earthquake caused by the release of methane from melting permafrost.

Here’s a new term: “Cli-Fi” = SF about climate change. Coined by Dan Bloom re: POLAR CITY RED: http://t.co/AkwFn3OE

— Margaret E Atwood (@MargaretAtwood) April 23, 2012

Bloom continued to document the genre’s rise on his website the Cli-Fi Report Global. The term took off after it appeared in two major news stories in 2013, one in The Christian Science Monitor and another on NPR, neither of which mentioned Bloom. Writing for The Guardian that same year, Rodge Glass said the term “went viral” after the NPR article. It quickly caught on in both the academic and literary worlds. In 2015, independent scholar Adam Trexler published Anthropocene Fictions: The Novel in a Time of Climate Change, the first in-depth review of novels dealing with human-caused climate change. In 2017, author Amy Brady began a regular assessment of cli-fi works and authors for the Chicago Review of Books. In 2019, Forrest Brown wrote that “it’s safe to say that climate fiction is now an established literary genre,” citing a “climate change fiction” category on Goodreads and a dedicated issue of the journal Guernica. In 2020, Jo Livingstone wrote for The New Republican that the preceding decade had seen a “steep rise in sophisticated ‘cli-fi’” such that the challenge for new authors was “standing out from the crowd (not to mention the headlines).” However, Bloom has argued that the genre will only continue to evolve and predicts a “Golden Age” in the 2050s to 2090s. “We are just at the beginning stages now and it is exciting to watch,” he said.

What Is the Relationship Between Climate Fiction and Ecofiction?

A related concept to climate fiction is ecofiction. Ecofiction emerged as a category in the 1960s and 70s in response to renewed scientific interest in ecology and the birth of the modern environmental movement. An early anthology, 1971’s Eco-Fiction, was edited by John Stadler. Its introduction said that ecofiction asked the questions, “Will man continue to ignore the warnings of the environment and destroy his source of life?” and “Will he follow the herd into the slaughterhouse?” A related concept to ecofiction is ecocriticism, which also emerged in the 1960s and is the academic study of how literature relates to the environment.

In Where the Wild Books Are: A Field Guide to Ecofiction (2008), scholar Jim Dwyer says that to be considered ecofiction, a work of writing must: 1. Depict the nonhuman environment as a “presence” that impacts human history and events; 2. Depict the nonhuman as a “legitimate interest” in addition to the human; 3. Include the idea that humans must be accountable to the environment; and 4. Depict the environment as a process rather than a static background. Works of ecofiction can cover all genres and styles, from John Steinbeck’s social realist novel about the Dust Bowl The Grapes of Wrath (1939) to Richard Powers’ lyrical, science-infused epic about the Pacific Northwest Timber Wars The Overstory (2018) to Cormac McCarthy’s post-apocalyptic The Road (2006). Scholar Patricia D. Netzley has divided ecofiction works into three categories: those that depict the environmental movement, those that depict a fight over a specific environmental issue, and those that depict a dystopia caused by ecological destruction. Climate fiction falls within the broader umbrella of ecofiction, but is a newer phenomenon linked specifically to awareness of and concern about human-caused changes to the climate. It’s probably safe to say that all climate fiction is ecofiction, but not all ecofiction is climate fiction.

What Are the Main Types of Climate Fiction?

Climate fiction encompasses a great variety of genres, styles, plots and approaches to human-caused climate change. However, there are a few dominant tropes and trends that have emerged in the past decade since it took off. The dividing line between these categories is not always sharp, as certain works may incorporate elements of all three. For example, there are works like Sam J. MIller’s Blackfish City (2018) that take place in post-apocalyptic settings but end on a hopeful note, or novels by critically acclaimed, literary writers that are set in a dystopian future but focus on the daily lives and relationships of a few characters, such as McCarthy’s The Road or T.C. Boyle’s A Friend of the Earth (2000).

Post Apocalyptic / Dystopian

From its emergence as a genre, climate fiction has been strongly associated with dystopian warnings of what a world that lets the climate crisis run amok might look like. In defining cli-fi, the website World Wide Words wrote that, “climate fiction is fundamentally dystopian. Its focus is the effect of climate change on human life, perhaps including its continuing existence.”

Paolo Bacigalupi’s novel The Water Knife. Alan Levine / Flickr

There are several examples of dystopian cli-fi works. The novel Bloom first marketed as cli-fi, Polar City Red, dealt with climate refugees in 2075 Alaska. Margaret Atwood’s MaddAddam Trilogy – Oryx and Crake (2003), The Year of the Flood (2009), and MaddAddam (2013) — has often been described as climate fiction, although the cause of her post-apocalypse is plague and biological engineering. One cli-fi author who has written several dystopian scenarios is Paulo Bacigalupi. His The Water Knife (2015) deals with conflict over the dwindling Colorado River in a drought-stricken Southwest. His young adult Ship Breaker trilogy begins with a young man who earns a living scavenging from abandoned oil tankers washed up on a future Gulf Coast. Another well-regarded dystopian work is Omar El Akkad’s American War (2017), which imagines a second civil war breaking out in the U.S. in 2074 after sea-level rise and the banning of fossil fuels.

Utopian / Solarpunk

While dystopian tales proliferate in cli-fi, several works have also been written in the tradition of utopian science fiction. An early progenitor is Ernest Callenbach’s 1975 work of utopian ecofiction, appropriately titled Ecotopia. The novel, set in an imagined 1999, follows a journalist who travels to report on the sustainable, feminist society created when Northern California, Oregon and Washington split from the U.S.

Perhaps the most prominent author writing in this tradition is Kim Stanley Robinson. Robinson has written a number of books that imagine in detail how human societies might respond technologically, politically and economically to climate change. His Science in the Capital trilogy — Forty Signs of Rain (2004), Fifty Degrees Below (2005) and Sixty Days and Counting (2007) — includes a flooding of Washington, DC and a mini-ice age brought about by a climate-induced stoppage of the Gulf Stream, but also imagines the election of a U.S. president who takes substantial steps to act on global warming. New York 2140 (2017) imagines a New York City that has flooded due to sea-level rise but has adapted and continues to thrive. The Ministry for the Future (2020) envisions how the goals of the Paris agreement might be put into practice. A major theme of Robinson’s work is “science over capitalism,” laying out how contemporary society might evolve away from a growth-based economic system that exploits the Earth and other humans into one that thrives within Earth’s planetary boundaries while addressing social and economic inequalities. Robinson has also said he has set out to fill an “empty niche in our mental ecology” between the world as it is now and the final utopia, focusing on how that transition might realistically occur.

One subgenre of climate fiction that is focused on positive solutions and hopeful futures is solarpunk. The term was first introduced in a 2008 blog post suggesting it as a new literary genre focused on a future that returned to, and innovated on, the renewable energy technologies of the past, such as sailing ships. The anonymous author nominated Norman Spinrad’s Songs From the Stars (1980) that depicted a society that ran only on energy from wind, sun, water and muscle. The idea took off as both inspiration for short story anthologies like the Brazilian Solarpunk: Ecological and Fantastical Stories in a Sustainable World (2012) and for an art nouveau-inspired visual aesthetic first shared by Miss Olivia Louise in 2014. It differs from traditional literary genres in that it has generated an online movement of people who also see themselves as actively working toward a solarpunk world, with art and literature as tools for building it. Solarpunk author Sarena Ulibarri describes it as “a shared vision of a future world, and a community in which everyone contributes in whatever way they can.”

Literary / Slice of Life

In his 2016 critical reflection The Great Derangement, novelist Amitav Ghosh argued that mainstream literary fiction — especially in the latter half of the 20th century — was especially ill-equipped to respond to the climate crisis. Because it had narrowed to focus on what John Updike termed the “individual moral adventure,” it could not respond adequately to collective experiences, let alone the agency of the non-human world. It is this inability to recognize the human world’s dependence on and vulnerability to the non-human that Ghosh termed “the great derangement.” “In a substantially altered world…” he wrote, “when readers and museum-goers turn to the art and literature of our time, will they not look, first and most urgently, for traces and portents of the altered world of their inheritance? And when they fail to find them, what should they… do other than to conclude that ours was a time when most forms of art and literature were drawn into the modes of concealment that prevented people from recognizing the realities of their plight?”

That said, there are, as Ghosh acknowledges, prominent literary authors who have incorporated the climate crisis into their novels. Many of these novels are set in or near the present that could still be described as “individual moral adventures.” Barbara Kingsolver’s Flight Behavior (2012) focuses on a dissatisfied Tennessee farm wife who stumbles upon a valley full of monarch butterflies whose migration has been diverted due to climate change. Nathaniel Rich’s Odds Against Tomorrow (2013) tells the story of a mathematician who works for an insurance company predicting worst case scenarios when a hurricane strikes Manhattan. Jesmyn Ward’s Salvage the Bones (2011) follows a Mississippi family as Hurricane Katrina bears down. Jenny Offill’s Weather (2020) is told from the perspective of a woman who gets a job responding to emails sent to a climate-change focused podcast. Pitchaya Sudbanthad’s Bangkok Wakes to Rain (2019) considers a large cast of characters whose lives intersect with a Bangkok house across different times, including a future in which parts of the city have been inundated by sea-level rise. As these few examples suggest, literary responses to climate change are coming to be as diverse and unique as artistic expression itself.

Climate Fiction on Screen

While write-ups and discussions of climate fiction often focus on written works, the term has also been used to describe visual storytelling, and several influential movies have shaped audiences’ perceptions of climate change. An early example was 1995’s Waterworld, in which Kevin Costner struggles to survive in a world that has flooded due to the melting of the ice caps. In 2004, disaster epic director Roland Emmerich turned his camera to a highly exaggerated depiction of what would happen if global heating were to trigger the collapse of the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation. In The Day After Tomorrow, what happens is a superstorm that ushers in another ice age. The film was notable because it was promoted by scientists and environmental activists who hoped it would encourage viewers to protest the climate denying policies of the Bush administration. (Its vice president was even a Dick Cheney look-alike who argues against climate action in the first act before having to apologize on live TV when the plot proves him wrong.) Geochemist Michael Molitor, who consulted on the film, said it would “do more for the issue of climate change than anything I’ve done in my whole life,” while MoveOn.org promoted it as “a movie President Bush doesn’t want you to see.”

Other notable films with climate themes include Pixar’s WALL-E (2008), in which the titular robot clears waste on a ruined Earth; Wanuri Kahiu’s Pumzi (2009), which imagines Africa’s regeneration after environmental catastrophe; Beasts of the Southern Wild (2012), set in a flooded-out Louisiana; Snowpiercer (2013), a dystopia about a world in which geoengineering to reverse global heating has resulted in an ice age; and Mad Max: Fury Road (2015), in which drought and desertification have enabled a warlord to gain power by controlling a dwindling water supply. Adam McKay’s 2021 satire Don’t Look Up used an impending comet strike as a metaphor for contemporary society’s refusal to acknowledge the risk of climate change, and the film inspired climate protesters to use the slogan, “Look up!”

Nonprofit Good Energy argues that even movies and TV shows that are not focused on the climate crisis should acknowledge it if they are set in the real world and the present day. “Climate change touches every aspect of life, so it’s only natural for it to show up in our stories, and for creators to include it in their work,” the group maintains. To that end, they have developed a Climate Reality Test for screenwriters, inspired by the Bechdel-Wallace test for depictions of women. The test asks two questions: does climate change exist in a story, and does at least one character know it. Good Energy surveyed the 13 fictional, feature-length Academy Award-nominated films for 2024 set in or near the present day in the real world and found that three of them, or 23%, passed the test. It wants to see 50% of present-day, real-world Academy Award-nominated feature films pass the test by 2027.

Does Climate Fiction Make a Difference?

Many writers and critics who engage with climate fiction see it as a way to alter our climate reality by offering a warning of a future to avoid or providing a roadmap toward a more just and sustainable society. Some argue that, because people have a hard time empathizing with their future selves, reading about and caring for characters contending with the climate crisis can help them make that imaginative leap and take action today.

There is some evidence that reading or watching films about the climate crisis might encourage action. One study found that people who watched The Day After Tomorrow were more likely to take climate risks seriously, to change their own behavior to reduce emissions and even to vote based on climate concerns. However, another study found that readers were more concerned about climate change immediately after reading two cli-fi short stories, but these concerns faded after a month. The author of the same study also warned that climate fiction narratives could backfire for writers who want to encourage climate justice: For example, some readers of The Water Knife expressed fear of — rather than empathy for — future climate migrants who would be desperate for amenities like regular water use that the readers take for granted.

Several writers who are included under the cli-fi umbrella have found it limiting or felt pressured to use it and have pushed back against the idea that their fiction should or could impact climate policy, pointing out that art is not the same thing as an op-ed or propaganda. Further, the decade that saw the rise of climate fiction also corresponded with the 10 hottest years on record, and the three main greenhouse gases also reached record levels in 2023. As author Matthew Salesses puts it, “If cli-fi acts as warning, and it is too late for warnings, what is the point?” Salesses’ answer is that future-oriented cli-fi can shake us out of our present reality sufficiently to help us survive the alterations to come. Stories can also make people more resilient to a more chaotic future, and writing and art are some of the ways that humans inevitably process the reality around them. As journalist Emma Pattee observes, “The rise of climate fiction isn’t happening in order to make us care about climate change; it’s happening because we already care.”

How Can I Learn More About Climate Fiction?

The books, films and analyses summarized in this article are only a fraction of the works of and responses to climate fiction out there. More climate fiction is also being written and published every day. Here are some resources you can pursue if you want to read more climate-inspired literature, or try your hand at writing some.

As a Reader

- The website dragonfly.eco hosts an in-depth database of ecofiction works, including climate fiction, as well as interviews with featured authors.

- The American Studies Journal has produced a bibliography of scholarly works on cli-fi.

- The website Literary Hub has curated a four-part climate change library, which it describes as “365 books that show us where we’ve come from, where we’re at now, how we might survive this crisis, and how we might cope if we don’t.”

- EcoWatch has published several lists of climate and environment-related books and movies, though not all are fiction.

As a Writer

- The website Grist runs a yearly short story contest called “Imagine 2200: Climate Fiction for Future Ancestors.”

- Solarpunk Magazine takes submissions of both fiction and non-fiction. Its upcoming submissions window for 2024 is October 1 to 14.

- EcoLit Books has an up-to-date list of journals and magazines that accept environmental writing, including fiction.

- The Climate Fiction Writers League is a group of cli-fi writers who accept applications to join their numbers.

Takeaway

There is a famous quote by Bertolt Brecht: “In the dark times / will there also be singing? / Yes, there will also be singing. / About the dark times.” Humans have always incorporated their reality into works of imagination, and climate fiction is just the most recent example. In many ways, the future of climate fiction will depend on the future of climate reality. Will policymakers, corporate leaders and ordinary people heed the warnings of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and make serious headway on a just transition away from fossil fuels by 2030, or will they and we continue to burn fossil fuels and clear forests, further raising temperatures, overturning tipping points and setting off ever more extreme weather events?

The decisions made now will determine whether humanity’s collective future looks more like solarpunk or The Water Knife, and therefore what that future’s creative output must grapple with. If humanity manages to get global warming under control and build a more equitable and sustainable society, future readers may look upon climate fiction as a historical curiosity, a warning of an apocalypse avoided. Or, if civilization as we experience it now is destroyed, the survivors may be left gathered around the dumpster fire, singing songs about the dark times.

The post Climate Fiction 101: Everything You Need to Know appeared first on EcoWatch.

0 Comments