This post was originally published on Eco Watch

More than a third of Africa’s great apes are being put at much greater risk from global mining activities than scientists had previously believed, according to a new study led by the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv).

The green energy transition’s increasing demand for critical minerals like copper, nickel, cobalt and lithium has led to a mining surge in Africa, a press release from iDiv said. This causes more deforestation in tropical rainforests — the habitat of great apes and many other species.

Chimpanzee habitat cleared for a railway to transport iron ore to a port in Guinea. Genevieve Campbell / iDiv

“Africa is experiencing an unprecedented mining boom threatening wildlife populations and whole ecosystems. Mining activities are growing in intensity and scale, and with increasing exploration and production in previously unexploited areas,” the study said. “Africa contains around 30% of the world’s mineral resources, yet less than 5% of the global mineral exploitation has occurred in Africa, highlighting the enormous potential for growth in this sector. Substantial production increases in the renewable energy sector are expected to cause a boom in mineral exploitation.”

As much as a third of the great ape population in Africa — almost 180,000 gorillas, chimpanzees and bonobos — could be threatened by mining, the study said.

The researchers pointed out that mining’s real impact on great apes and biodiversity in general could be even higher, since there is no requirement that mining companies make biodiversity data available to the public, the press release said.

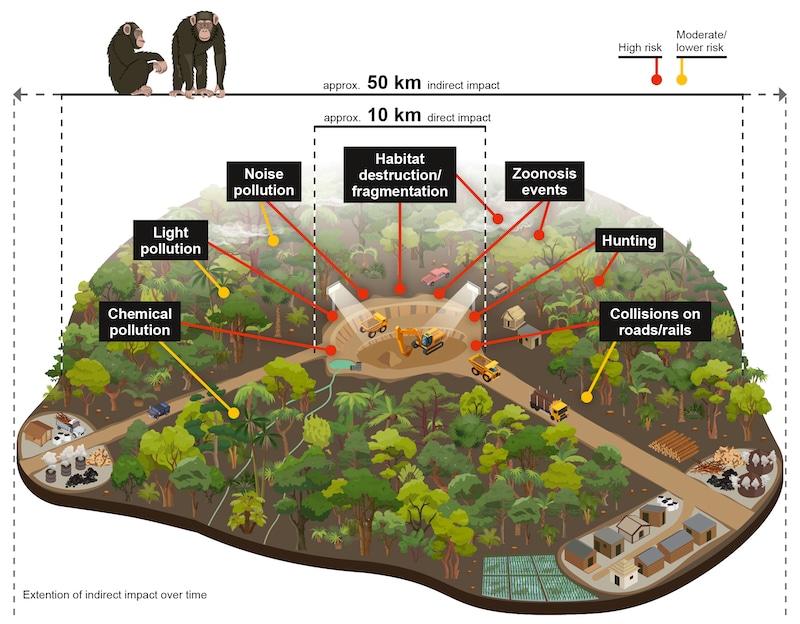

For the study, the research team used data on mining sites in 17 countries in Africa. The team defined 6.21-mile buffer zones to measure direct impacts like noise and light pollution and habitat destruction. They also defined 31.07-mile buffer zones to look at indirect impacts associated with increased human activity, such as roads and infrastructure built to access previously remote areas. This new development puts increased pressure on great apes from habitat loss, hunting and a greater risk of disease transmission.

The team used the African great ape density distribution data to investigate how many apes could be negatively impacted and made maps of areas where high ape densities overlapped with frequent mining.

“Currently, studies on other species suggest that mining harms apes through pollution, habitat loss, increased hunting pressure, and disease, but this is an incomplete picture,” said Dr. Jessica Junker, lead author of the study, researcher for Re:wild and a postdoctoral researcher at Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg’s Institute of Biology and iDiv, in the press release. “The lack of data sharing by mining projects hampers our scientific understanding of its true impact on great apes and their habitat.”

The largest overlaps of mining sites and areas with high ape density in both buffer zones were in the West African countries of Sierra Leone, Mali, Guinea and Liberia. The biggest overlap of chimpanzee density and mining was in Guinea, where as much as 83 percent of the ape population — more than 23,000 chimpanzees — could be impacted by mining activities either directly or indirectly.

Overall, areas with relatively high mining and ape densities were not protected.

The study, “Threat of mining to African great apes,” was published in the journal Science Advances.

The research team also looked at the intersection of mining areas with “Critical Habitat,” which consist of regions that are essential because of their unique biodiversity apart from apes. The team discovered a 20 percent overlap between these. Designation of critical habitat necessitates strict environmental regulations, particularly for those mining projects that are seeking funding from the International Finance Corporation — part of the World Bank — and other entities that adhere to similar standards and are looking to operate inside these zones. Earlier efforts to map Africa’s critical habitat have failed to include major areas of ape habitat that could qualify under global benchmarks.

Direct and indirect impacts of mining on great apes in Africa. Gabriele Rada / iDiv

“Companies operating in these areas should have adequate mitigation and compensation schemes in place to minimize their impact, which seems unlikely, given that most companies lack robust species baseline data that are required to inform these actions,” said Dr. Tenekwetche Sop, who manages Senckenberg Museum of Natural History’s IUCN SSC A.P.E.S. database — a repository of population data on all great apes — in the press release. “Encouraging these companies to share their invaluable ape survey data with our database serves as a pivotal step towards transparency in their operations. Only through such collaborative efforts can we comprehensively gauge the true extent of mining activities’ effects on great apes and their habitats.”

Although these impacts are hard to quantify, they frequently extend far beyond a mining project’s boundaries, and mining companies rarely consider or take steps to mitigate the risks. Furthermore, offset or compensation is based on approximate impacts, which researchers say are often underestimated and inaccurate. And while offset programs generally last only the length of the mining project, most impacts from mining on great apes are not temporary.

“Mining companies need to focus on avoiding their impacts on great apes as much as possible and use offsetting as a last resort as there is currently no example of a great ape offset that has been successful,” explained Dr. Genevieve Campbell, senior researcher at Re:wild and head of the IUCN SSC PSG SGA/SSA ARRC Task Force, in the press release. “Avoidance needs to take place already during the exploration phase, but unfortunately, this phase is poorly regulated and ‘baseline data’ are collected by companies after many years of exploration and habitat destruction have taken place. These data then do not accurately reflect the original state of the great ape populations in the area before mining impacts.’’

Junker emphasized that the best way to protect great apes and biodiversity is to let them be.

“A shift away from fossil fuels is good for the climate but must be done in a way that does not jeopardize biodiversity. In its current iteration it may even be going against the very environmental goals we’re aiming for,” Junker said. “Companies, lenders and nations need to recognize that it may sometimes be of greater value to leave some regions untouched to mitigate climate change and help prevent future epidemics.”

The post Africa’s ‘Mining Boom’ Threatens More Than a Third of Its Great Apes appeared first on EcoWatch.

0 Comments